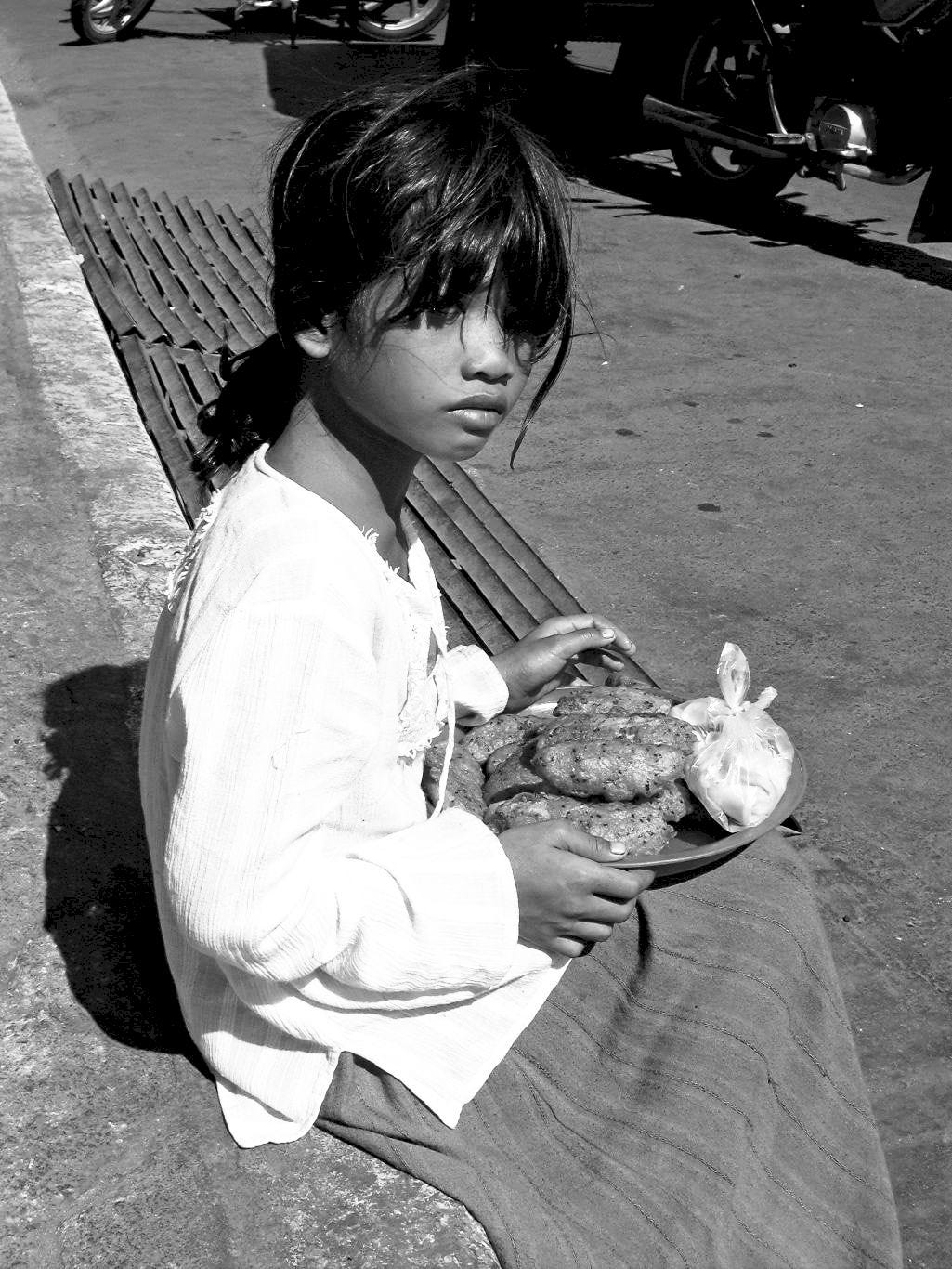

Photo credit: "child selling food on the street" by mrcharly is marked with CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.

One of my hobbies vices is collecting old cookbooks. I probably have four or five hundred of them in my basement, and I’ve spent enough time researching them in my life to be an expert about certain narrow slices of food literature. Yet there are many, many areas of food life that I’m completely in the dark about.

One prime example is “What do French people cook at home?” In American popular imagination, French food is high-class, arguably the world’s best cuisine.

Or at least it was in 1983. But I digress.

There’s a certain trust-fund element of food writer who will be happy to enlighten you about what French people eat because they spent a year in Provence, following/harassing everyone’s maman as she prowled the markets looking for the freshest, the tiniest, the best of everything, then burying it in so many fine herbes you suspect it was cooked underneath a Lawn-Boy. I’m sure this sort of fauxletarian writing has helped many a failson and/or faildaughter get an MFA back in the 1980s, but I’m fairly certain the typical French person is not a rural grandmother, so no thanks. What do families in the Paris suburbs eat on a Thursday night in January? That question is hard for me to answer, probably because I stopped studying French in high school.

It’s moot anyway. In 2022 your MFA project can’t be so Eurocentric, so blanc des blancs, as an examination of French home cooking. Peasant food had a lengthy stay as the trendy cuisine among cuisine trendoids1 so now there’s also a lot of literature about what the poor eat all over the world, and most of it is terrible. (The writing, not the food.) I even have in my collection a book written by a couple who traveled the world studying rice. Rice. An entire book about rice and how it’s eaten all over the world. It is a less fascinating topic than one might think.

My professional life intersects with food. We run a food pantry. The topic of hunger is a very personal one to me. I’ve never experienced it, but I was an adult before I realized that the reason no one brought their lunch to my school was because they were getting it free or at a reduced price.

And that’s how I began to explore the question “What do poor people eat?”

My cookbooks are of limited help with this question. Most of them are from the US in the mid-to-late 20th century, the era of abundance, victory, and convenience foods. Their goal was not so much to help people figure out how to cook as it was to shape and steer the cook’s imagination to bigger, easier meals with more consumer products. That’s fine by me; I am and always will be a capitalist. But it means such cookbooks have little reflective value. They don’t show us what people ate; they show us what corporations like General Mills (Betty Crocker) and Meredith Publishing (Better Homes and Gardens) wanted them to eat. So the “budget” sections of those cookbooks had three recipes for liver.

The other reason cookbooks aren’t much help figuring out what poor people eat is because you can’t sell cookbooks to poor people; they don’t have the money for them. If they buy cookbooks at all, it’s at thrift stores. Every thrift store book section I’ve ever seen has multiple microwave cookbooks from the late Seventies and early Eighties, before we figured out that microwaves are a lot better at reheating food than they are at cooking it. This means that somewhere out there is a poor family that learned the hard way you can’t microwave a turkey.

The peasant-food MFAs are happy to tell you that poor people the world around eat seasonal produce and small amounts of meat and would never listen to the Eagles, drive a Suburban or vote Republican, and wouldn’t the world be a better place if we all “opted out” of American life and followed their example? Those things are all true but largely irrelevant. They eat seasonal produce because they lack refrigeration. They eat small amounts of meat because they are poor and can’t afford more.

Here in the US we look at our poor and wonder if food security is even an issue, since so many of them appear to be, um, “doing well.”2 Hidden is the reality that calories are cheap but nutrients are (relatively) expensive, so the leaner you are, the more likely you are to be fairly high up the socioeconomic scale. There are habits that develop because, while you can go under your vitamin A requirements for a long, long time without serious side effects, low blood sugar will take you down pretty quickly.

We see this at the food pantry. The first stuff out the door is anything that’s ready to eat, particularly if you don’t need a can opener for it. Canned pasta in pull-top cans will go right away. Ditto ready-to-eat soup. But we literally cannot give away dried beans. That’s a shame because they’re shelf-stable, sustainable, highly nutritious, way easier on the environment than any sort of meat, and dirt cheap. (Theologically you can make the case that God created beans so that the poor would never have to go hungry and could even be healthier than kings.) And I’m in the South, where ham and beans is a way of life. Still can’t give them away. Not even to unemployed people who have the time to soak and cook them. I know it doesn’t make sense, but facts are facts.

Thank God, literally, that not all the writing about “poverty food” has been done by trust-find MFAs cosplaying solidarity. Two cookbooks in my collection treat the issue with seriousness — and they were both published by the Mennonite Central Committee. (You should buy any cookbook with “Mennonite” in the title, IMO, though interestingly neither of these do.)

The first, The More-With-Less Cookbook, was written by a Mennonite woman named Doris Janzen Longacre and published in 1976. In it the question of rising food prices and declining nutrition is front and center, making this an important book for our time as well. Important enough that the MCC revised and updated the book, for what it’s worth, even though it had been in print constantly since 1976. The contents of the book are a glimpse into the American alternative mindset of the mid-Seventies, when environmentalism was less political but centered more on personal consumption. Longacre decries the excess consumption of protein, particularly meat, describing it as wasteful and harmful to the environment, which it is. I have not read the updated version but I’d like to.

However, that book dealt with what Christians making choices to live simply ate. It’s not wrong, per se, but it lacks an understanding of involuntary poverty. The followup, Extending the Table, does not lack that understanding at all. A collection of recipes gathered by Mennonite missionaries, Extending the Table might be the only book in my collection to show how poor people all over the world really eat.

Quite well, as it turns out; if their diets lack variety, they at least know how to keep their bellies full. The recipes don’t commit the cardinal sin of telling the story of poor-person’s food from a rich person’s perspective. If the people in Botswana use canned vegetables for a stew, it tells you so.

The stories told by the missionaries are equally heartwarming and heartbreaking. Desperately poor people sharing the little they have and being glad to do so because they understand how interwoven we all are: I help you today because I may need your help tomorrow. Airline plates and forks being reused for special occasions. Meals served on banana leaves — or frisbees. A groundskeeper who has to baby his colonialist boss’s dogs but gets little sympathy when his own child dies. A family that can’t afford to feed all their children, so they choose one to starve. (A cookbook shouldn’t put tears in your eyes or make you want to punch out an industrialist, but this one does.) And oh, the prayers; they make my table graces sound as Mickey Mouse as I’m sure they are.

My point in writing this was not to shame you for being wealthy or signal my own virtue (I have none to signal) or even to brag about my collection. I just want you to think a little more deliberately about food and its importance not just in your own life but in everyone’s. All food is sacred, and God be with the hungry.

They’ve moved on to plant-based everything, of course, because the world needs dissertations about someone’s attempt to create a “Big Mock.”

So do I, FWIW.